Forensic Toxicology Services

Scientific Expertise for the Legal Community

About FTS

Forensic Toxicology Services

(FTS) is a scientific resource for the legal community in the areas of forensic toxicological analysis and interpretation. FTS is no longer accepting casework or providing consultation services but remains available for educational activities. Professional referral is available. FTS is located in Birmingham, AL.

Contact an Expert

Toxicology

is the study of drugs and poisons and their effects on the health and/or performance of the consumer.

Forensic Toxicology

is the application of toxicological principles to medical-legal issues such as cause and manner of death and subject performance or behavior relating to criminal and other regulated activity.

Toxicological Testing

is a laboratory-based process whereby specimens are examined for substances of toxicological significance (drugs, alcohols, poisons). Test findings based upon proficient laboratory analyses are scientifically accurate and reliable. Variables such as, but not limited to specimen source, collection, timing, custody, maintenance, availability and condition do not effect scientific accuracy and reliability unless they disrupt the testing process.

It is what it is.

Read More

Toxicological Interpretation

is a post-testing, non-laboratory process whereby the significance of test findings is examined in relation to the context of the case. Variables such as, but not limited to specimen source, collection, timing, custody, maintenance, availability and condition can affect the interpretation of otherwise scientifically accurate and reliable test findings.

But it could mean something else.

Read More

Expertise

Pain, Prison, Postmortems

I see humanity ease melancholy with insobriety

Gluttony unleash revelry, calamity, tragedy

Addiction, infirmity, need for remedy

Reality, finality, a bag for everybody

Pain, prison, postmortems

Misery run deep

I atone with all sincerity

Imply no indignity

Cope with levity

Lest I weep

A... as in apple autopsy

"This was the most unkindest cut of all"

- Marcus Antonius/William Shakespeare

"Helping neighbor look for gas leak under his trailer

Lit match to detect gas leak

BOOM

Refused medical attention

Later showed up at hospital complaining of burns

Autopsy"

"You know I've smoked a lot of grass

O' Lord, I've popped a lot of pills

But I never touched nothin'

That my spirit could kill"

- Hoyt Axton/Steppenwolf

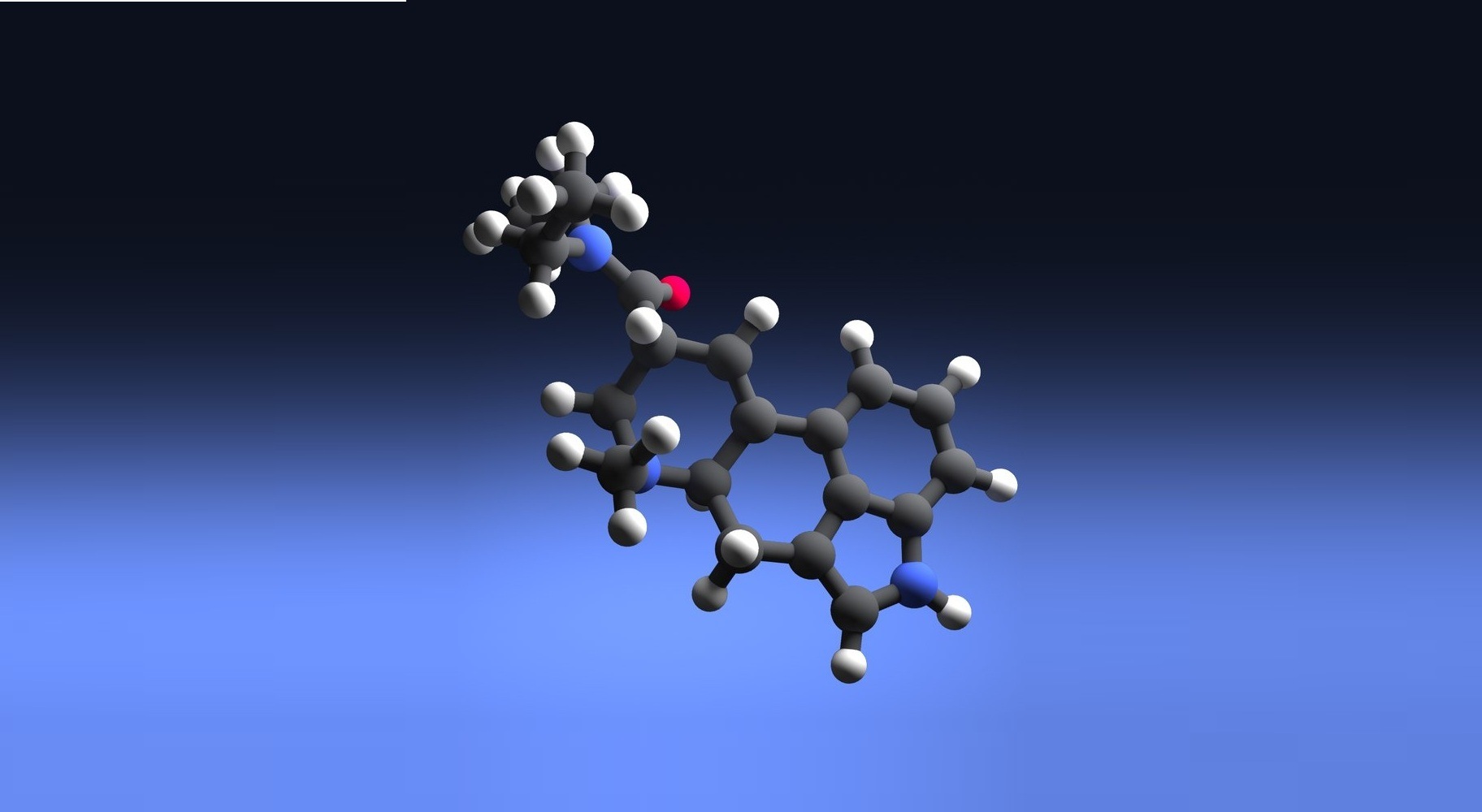

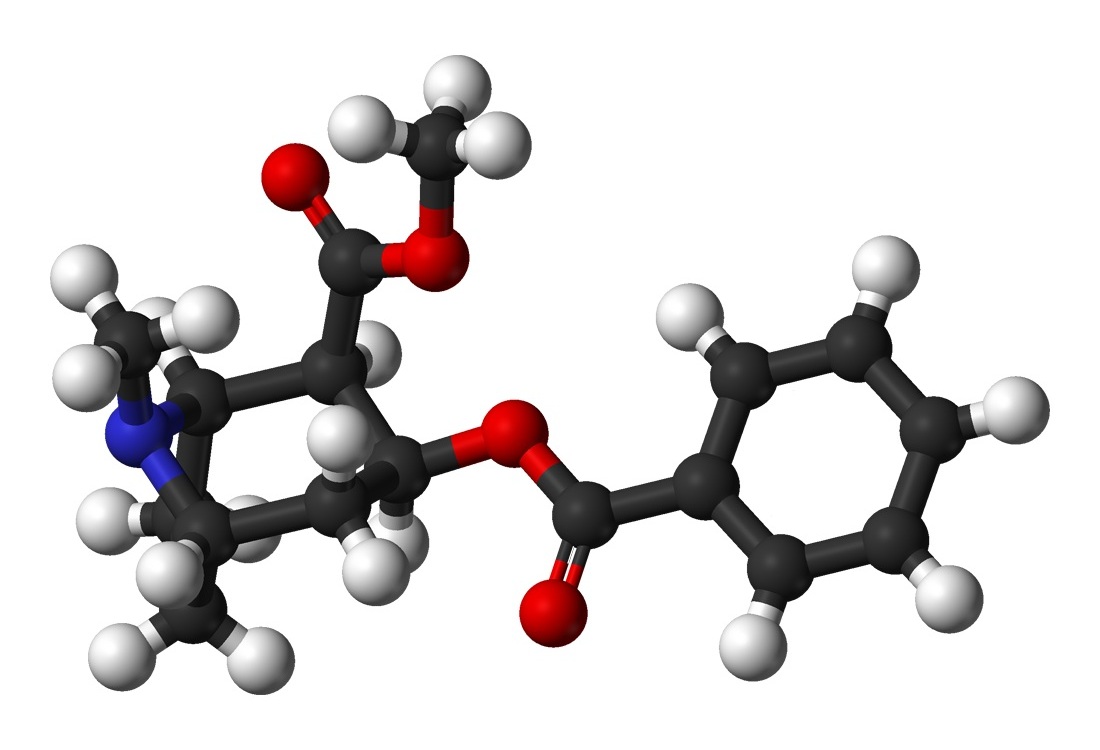

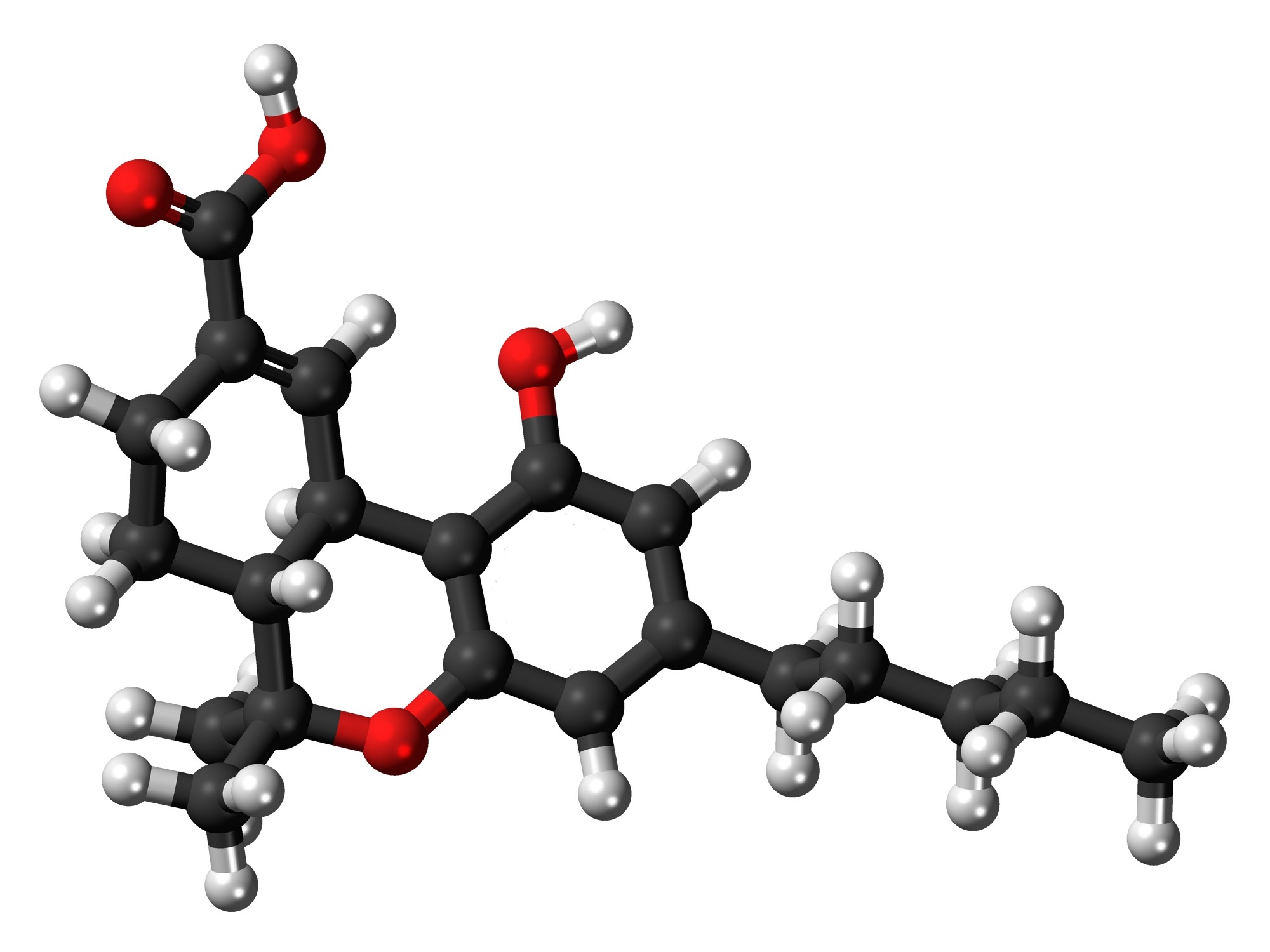

A scientist's view of morphine

"I've seen the needle and the damage done

A little part of it in everyone

But every junkie's like a settin' sun"

- Neil Young

"One pill makes you larger

And one pill makes you small

And the ones that mother gives you

Don't do anything at all

Go ask Alice

When she's ten feet tall"

- Jefferson Airplane

These don't come with warnings

"If you wanna hang out

You've got to take her out

Cocaine

If you wanna get down

Down on the ground

Cocaine

She don't lie

She don't lie

She don't lie

Cocaine"

- John Cale/Eric Clapton

"Gramma gets that way on crack"

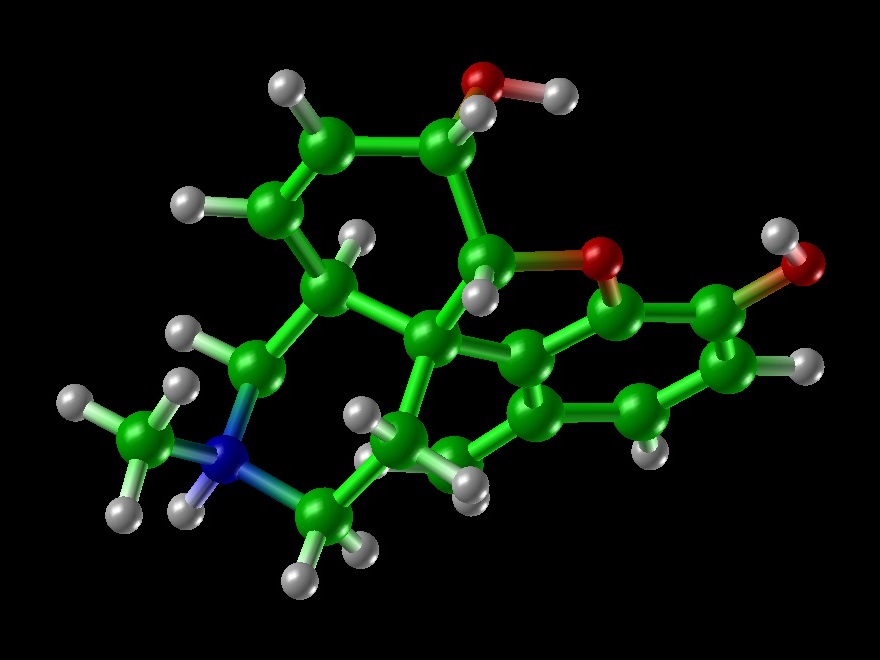

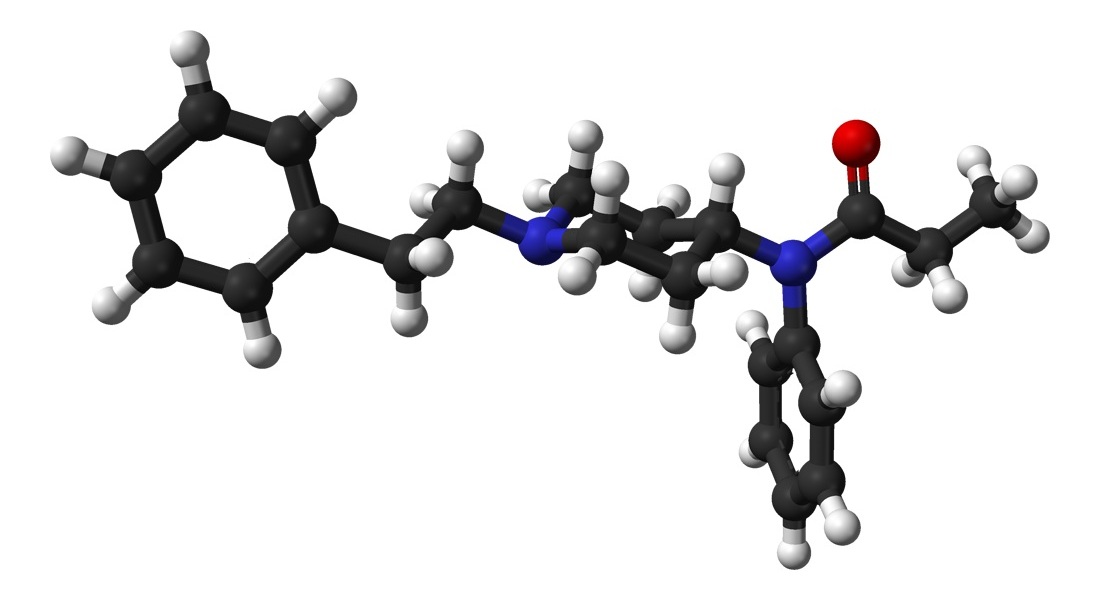

A scientist's view of cocaine

"I'm your mama, I'm your daddy

I'm that n**** in the alley

I'm your doctor when in need

Want some coke? Have some weed

You know me, I'm your friend

Your main boy, thick and thin

I'm your pusherman

I'm your pusherman"

- Curtis Mayfield

"Driving that train, high on cocaine

Casey Jones you better watch your speed

Trouble ahead, trouble behind

And you know that notion just crossed my mind"

- Grateful Dead

"Perhaps you’d understand it better

Standin’ in my shoes

It’s the ultimate enticement

It’s the smuggler’s blues

It’s a losing proposition

But one you can’t refuse

It’s the politics of contraband

It’s the smugglers blues"

- Glenn Frye

A scientist's view of fentanyl

"Oh, I get by with a little help from my friends

Mm, I get high with a little help from my friends

Mm, gonna try with a little help from my friends"

- Joe Cocker/Beatles

You can die with a little help from your friends

Say hello to my friends

"Well, my baby, she gone, gone tonight

I ain't seen the girl since night before last

I wanna get drunk, get off of my mind

One bourbon, one scotch, and one beer"

- Amos Milburn

- John Lee Hooker

- George Thorogood/The Destroyers

Judge: Looks here like you were drinkin’

Defendant: No, I was fishin’

Judge: What do you do when you go fishin’?

Defendant: I cool off with beer

Judge: I call that drinkin’

Defendant: Nope, drinkin's when you’re in a bar

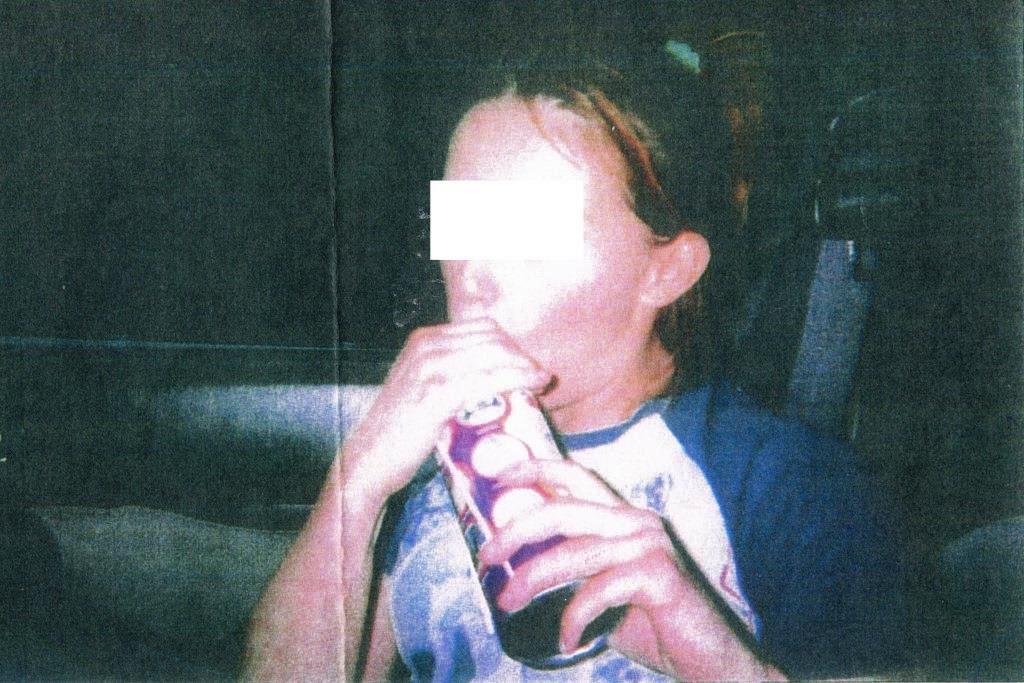

A first responder's view of ethanol

"Pour me somethin' tall an' strong

Make it a "Hurricane" before I go insane

It's only half-past twelve but I don't care

It's five o'clock somewhere"

- Alan Jackson

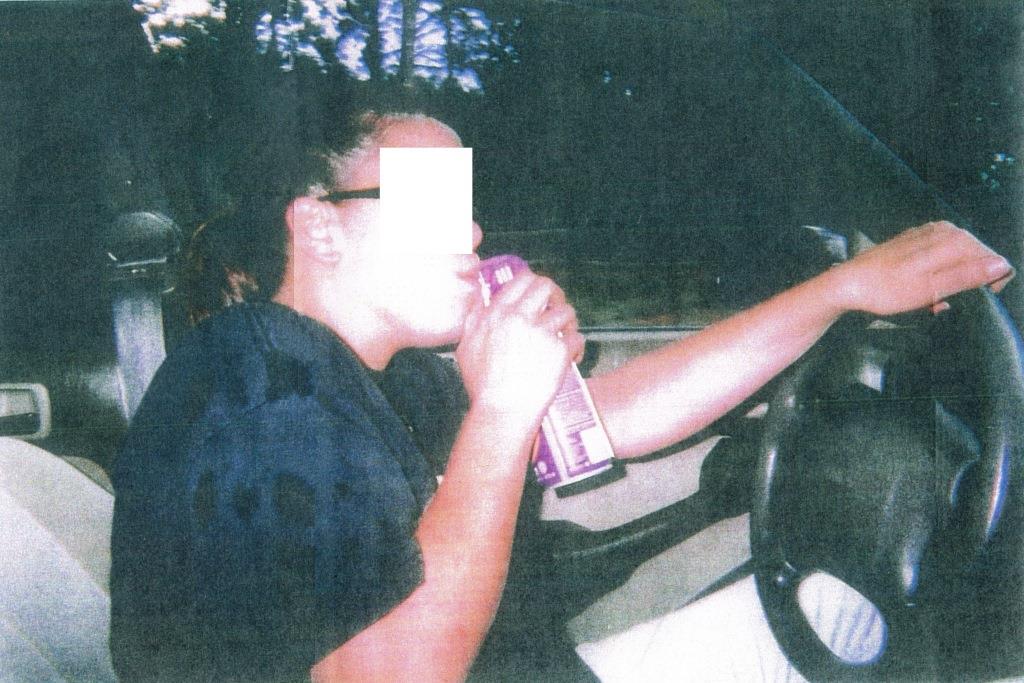

We're not supposed to drink and drive

Yet we have beer-branded key rings

"Oh, show me the way to the next whiskey bar

Oh, don't ask why, no, don't ask why

For we must find the next whiskey bar

Or if we don't find the next whiskey bar

I tell you we must die, I tell you we must die

I tell you, I tell you, I tell you we must die"

- The Doors

We're not supposed to drink and drive

Yet we have bottle opener key rings

"It's nine o'clock on a Saturday

The regular crowd shuffles in

There's an old man sittin' next to me

Makin' love to his tonic and gin

And the waitress is practicing politics

As the businessmen slowly get stoned

Yes, they're sharing a drink they call loneliness

But it's better than drinkin' alone"

- Billy Joel

"I ain't as good as I once was

That's just the cold hard truth

I still throw a few back, talk a little smack

When I'm feelin' bullet proof

So don't double dog dare me now

'Cause I'd have to call your bluff

I ain't as good as I once was

But I'm as good once as I ever was.

May not be good as I once was

But I'm as good once as I ever was."

- Toby Keith

"I'll learn to work the saxophone

I'll play just what I feel

Drink Scotch whiskey all night long

And die behind the wheel

They got a name for the winners in the world

I'll want a name when I lose

They call Alabama the Crimson Tide

Call me Deacon Blues"

- Steely Dan

"It's a tough ol' life up here on the wagon

I'm feedin' the dog, sackin' the trash

It's honey do this honey do that

I sobered up, and I got to thinkin'

Girl you ain't much fun since I quit drinkin'

Yeah I sobered up, and I got to thinkin'

Girl you ain't much fun since I quit drinkin'"

- more Toby Keith

"I blew out my flip-flop, stepped on a pop top

Cut my heel, had to cruise on back home

But there's booze in the blender

And soon it will render

That frozen concoction that helps me hang on

Wastin' away in Maragaritaville..."

- Jimmy Buffet

"I love this bar

It's my kind of place

Just walkin' through the front door

Puts a big smile on my face

It ain't too far, come as you are...

And we like to drink our beer from a mason jar

Hmmm, hmmm, hmmm, hmmm, hmmm I love this bar"

- more Toby Keith

"All week long we're some real nobodies

But we just punched out, it's paycheck Friday

Weekend's here, good God almighty

People let's get drunk and be somebody"

- more Toby Keith

"No, no, no, no, I don't (sniff) it no more

I'm tired of waking up on the floor

No, thank you, please

It only makes me sneeze

Then it makes it hard to find the door"

- Hoyt Axton/Ringo Starr

What's it gonna be?

[Sniff] Hit me again.

[Sniff] And one for my friend.

"And here, she's acting happy

Inside her handsome home

And me, I’m flying in my taxi

Taking tips, and getting stoned

I go flying so high, when I’m stoned"

- Harry Chapin

"Don't bogart that joint my friend

Pass it over to me"

- Fraternity of Man

A scientist's view of THC

"One toke over the line, sweet Jesus

One toke over the line

Sitting downtown in a railway station

One toke over the line"

- Brewer and Shipley

- Lawrence Welk

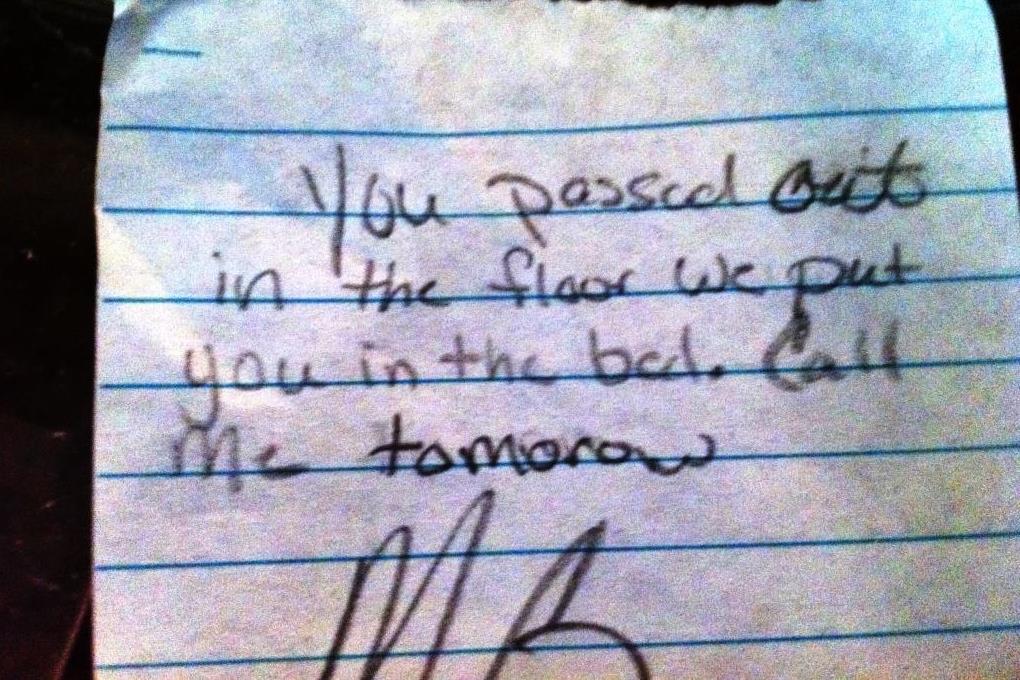

"Some radio is blastin'

Someone's knockin' at the door

I'm lookin' at my girlfriend

She passed out on the floor

I've seen so many things

I ain't never seen before

Don't know what it is

I don't wanna see no more"

- Randy Newman

- Three Dog Night

"Think I'll spend eternity in the city

Let the carbon and monoxide choke my thoughts away, yeah

And pretty bodies help dissolve the memories

They can never be what she was (was) to (to) me"

- Hall and Oates

"Every night I go to sleep

The blues fall down like rain

Taking pills, cheap whiskey

Just to try to ease the pain"

- Blues Brothers

"Well, I woke up this mornin'

And I got myself a beer

Well, I woke up this mornin'

And I got myself a beer

The future's uncertain

And the end is always near"

- more Doors